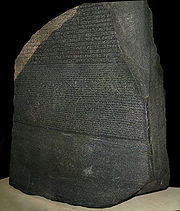

Until its decipherment by the French philologist Jean François Champollion (1790-1832) in the early 1820s, the nature of Egyptian writing system eluded European scholars. The impressive naturalism of the pictographs as well as a number of misconceptions handed down from antiquity led them to believe that the script was symbolic and that each one of the so-called 'holy characters' - which is what 'hieroglyph' means - was to be interpreted as a word, if not an entire sentence. As it turned out, only few Egyptians signs are logograms. Champollion arrived at the conclusion that Egyptian hieroglyphs were a phonetic rather than symbolic script when he analysed the Rosetta Stone, a stele dating from 196 BCE, which is inscribed in two languages, Greek and Egyptian, and three scripts, the Greek alphabet, and the hieroglyphic and demotic varieties of Egyptian. Counting Egyptian signs and Greek words, he found that there were 1,419 signs for 486 words. Since the 1,419 were made up of only 66 different signs, he correctly concluded that the script was phonetic, at least in part.

After Champollion's path-breaking discovery, the detail of the system were worked out. It is a mixed system consisting of phonograms of various sorts and signs that are interpreted for meaning rather than sound. All in all some 700 signs were used to write the language during its classical period in the second millennium BCE, although the total number increased significantly in later periods. However, more than 400 signs were rarely needed at any one time. In addition to the pictorial hieroglyphs that are always used to monumental inscriptions, the Egyptians developed two more cursive script forms for manuscript writing, which allowed for greater speed and efficiency: the semicursive 'hieratic' and the cursive 'demotic', both so called by the Greeks. The iconic properties of the hieroglyphs were lost in these cursive scripts, but structurally they remained fairly close to the hieroglyphic model.

One important difference between the hieroglyphic script and the two cursive scripts has to do with the grouping and combination of signs. While hieratic and demotic writing is always linear from right to left, there is often no such clear correspondence between the flow of speech and the linearity of the hieroglyphic script. The arrangement of hieroglyphs makes more liberal use of the two dimensions of the writing surface, often closely integrating the written text with graphic images relating to its contents. Both the orientation of the hieroglyphs and their spatial arrangement in columns and horizontal lines is more varied and flexible than hieratic and demotic writing. Hieroglyphs are sometimes switched in their order for reasons of better spacing (Davies 1987: 13).

A defining feature of the Egyptian writing system is that it provides no overt cues for the interpretation of vowels (Schenkel 1984). Egyptian belongs to the Hamito-Semitic family of languages, which is characterized by triconsonantal word-roots. Other writing systems for Semitic languages also focus on consonants but like the North Semitic cuneiform systems and the consonant alphabets of the Phoenician family of scripts, the Egyptian script has no auxiliary means of vowel indication. On the basis of consonantal frames readers supply the contextual appropriate vowels to interpret the full body of the word.

To this end they make use of the three classes of signs that, as all available evidence suggests, were present in the earliest stages of the Egyptian script around 3000 BCE (Fischer 1989) and used continuously until the end of its long history in the tenth century CE. There three classes of signs are logograms, phonograms and determinatives.

(Writing Systems: An introduction to their linguistic analysis, Florian Coulmas)